Shallow Versus Deep Foundations: Factors to Consider, Common Mistakes and Pitfalls, and More

View the complete article here.

The significance of foundations goes beyond merely supporting the load above—they ensure structures remain steadfast amidst varying environmental conditions, ensuring the safety and longevity of the buildings we live and work in.

There are primarily two types of foundations that are predominantly used in construction: shallow and deep foundations. Each type has its unique attributes and applications—influenced by a myriad of factors like soil conditions, bearing capacity, structural demands, site limitations, and financial considerations—to name a few.

By understanding their distinct characteristics and the scenarios where foundations are most aptly employed, contractors and engineers can make informed decisions tailored to their project’s needs. We will also shine a spotlight on some of the most prevalent mistakes and pitfalls associated with each foundation type, ensuring that you’re equipped with the knowledge to navigate your next foundation project.

Shallow Foundations

Shallow foundations, often referred to as “spread footings” or “open footings,” are those that transfer the building’s load directly to the earth near the surface—rather than to subsurface layers or a range of depths as deep foundations do. The main characteristic of shallow foundations is that the depth at which they are placed is generally less than the width of the footing itself.

Shallow foundations are used when the load of the structure is “light” compared to the strength of the surface soils. They are most commonly used for structures like single to two-story houses and low-rise commercial buildings. These types of foundations are popular due to their simplicity and cost-effectiveness.

Types of Shallow Foundations

Strip footings are continuous footings that support a linear structure like a wall. They spread the load over a large area, usually the entire length of the wall, ensuring the weight is well-distributed and the pressure on the soil remains within acceptable limits.

Also known as isolated footings, spread footings are individual footings used to support point loads like columns. They can be square, rectangular, or circular in shape and distribute the structural load over a specific area to the underlying soil.

When individual footings cover more than half the foundation area, it might be economical to provide a single mat (or raft) foundation. This is a large slab supporting all the columns, distributing the loads across its entire area.

Equipment and Techniques Used for Shallow Foundations

Shallow foundations require excavation to reach the desired depth, and excavators are crucial for this. They efficiently remove the soil, preparing the site for the foundation.

After excavation, the site might need leveling or grading to ensure a uniform surface for the foundation. Bulldozers are employed to achieve this level surface, ensuring the foundation rests on a stable base.

Once the site is prepared, concrete is poured to form the foundation. Concrete mixers play an essential role in ensuring the concrete is uniformly mixed and ready for pouring.

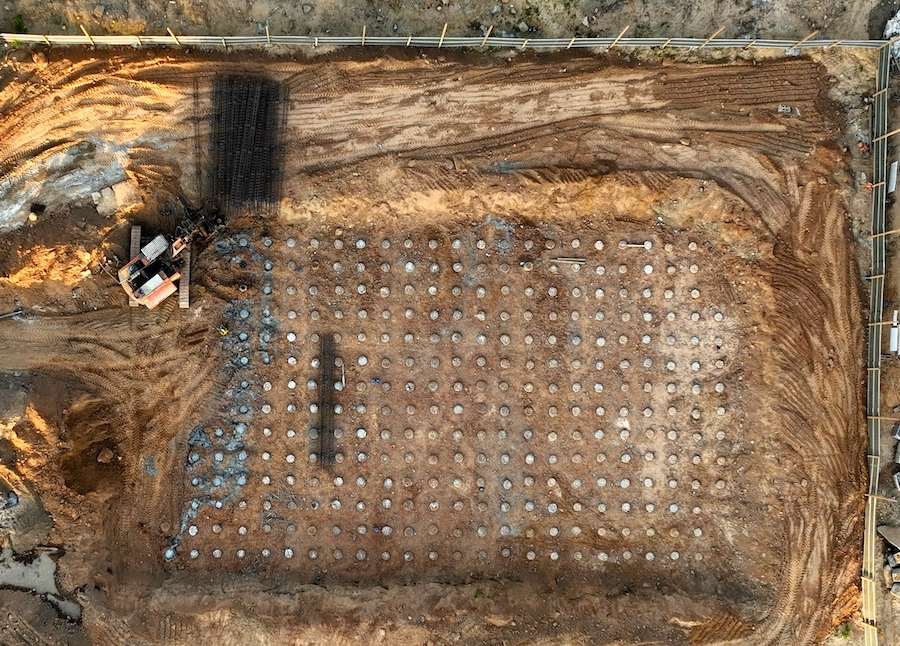

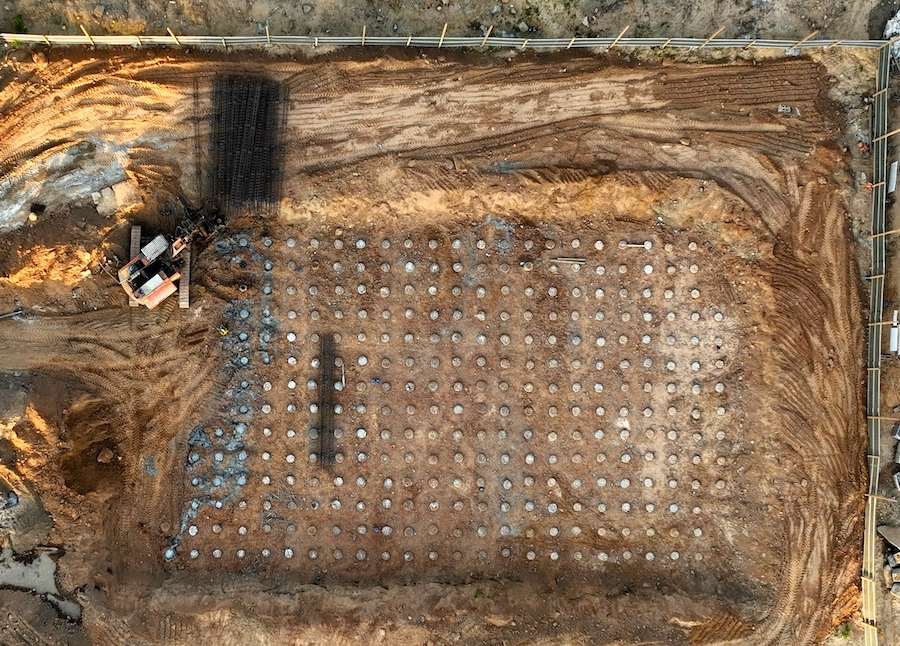

Deep Foundations

When surface soils lack the strength or are too compressible to support structures directly, engineers and builders turn to deep foundations. These foundations transfer loads from structures through weak layers down to stronger soil layers or even rock.

Deep foundations are essential when the bearing capacities of surface soils are inadequate to support loads imposed. They are typically are utilized for large structures, bridges, tall buildings, and in areas with challenging soil conditions like marshes or those with liquefaction potential during an earthquake. The depth of these foundations often exceeds their width, and they are driven, bored, or cast in place to depths that ensure stability.

Types of Deep Foundations

Piles are long, slender members made from concrete, steel, or timber. Depending on their installation technique and purpose, they are categorized as:

- Driven piles: Installed by hammering into the ground.

- Bored piles: Formed by drilling a hole in the ground and then filling it with concrete.

- Screw piles: Installed by rotating or screwing into the ground.

Caissons and drilled shafts are watertight retaining structures used mainly for bridge piers and abutments in rivers, lakes, or other water bodies. They are drilled into the ground and, once they reach the desired depth, are filled with concrete.

Piers are vertical supports for arches or bridges, often extending deep into the ground to offer stability in challenging terrains or conditions.

Methods of Pile Installation:

With the driving method, piles are hammered into the ground using various techniques:

- Drop hammer: A heavy weight is lifted and then released to fall freely onto the pile.

- Single-acting hammer: Works using steam or air pressure.

- Double-acting hammer: Uses both the up and down stroke.

- Vibratory drivers: Use vibrations to reduce the resistance of the ground and drive the pile.

Boring involves drilling into the ground using techniques such as:

- Auger drilling: Uses a helical screw to drill the ground.

- Continuous flight auger (CFA) piles: Combines drilling and piling in one operation without needing to extract soil.

- Screwing: This technique utilizes hydraulic torque motors to rotate or screw the pile into the ground.

Equipment Used for Deep Foundations:

Some of the most common equipment used for deep foundation work includes, but is not limited to:

- Pile drivers: Pile driving is achieved through dropping heavy weights, or hammers, onto the pile or using hydraulic methods. Pile drivers are essential when the objective is to transfer the building’s load to a deeper, more stable layer of soil or bedrock.

- Drilling rigs: Drilling rigs are employed to create deep holes in the ground for bored piles and caissons. They come with various capacities and functionalities tailored to specific soil conditions and project requirements.

- Vibratory hammers/extractors: This equipment is used for both the penetration of piles in dense soils through high-frequency vibratory forces and for the extraction or correction of piles by applying a pulling force, ensuring minimal damage to the piles.

- Cranes: These are indispensable in deep foundation projects, especially for larger-scale undertakings. Cranes are utilized for lifting, positioning, and placing piles at the designated points. They offer versatility and come in various sizes and capacities.

- Augers and drills: Augers and drills are crucial for removing soil and creating holes for piles. Their designs range from simple hand-held versions to large mechanized units, depending on the project’s scale.

- Hydraulic power packs: These are external power sources providing the necessary hydraulic energy to various foundation equipment, especially when onboard power sources might not suffice.

- Pile cutters: After the installation of piles, they often need to be trimmed to the desired level. Pile cutters are employed to achieve a clean and precise cut, ensuring uniformity and structural integrity.

Factors to Consider when Choosing a Foundation Type

Needless to say, the right foundation is paramount for the stability and longevity of a structure. The foundation type not only determines the structural integrity but also impacts the construction’s economic viability and environmental sustainability. Here are key factors every engineer and contractor should consider pertaining to choosing a foundation type…

Soil Type and Bearing Capacity

Soil is the primary connection between the structure and the earth, and its properties significantly influence foundation design. Different soils have varying strengths, compressibility, and expansion potential. By conducting geotechnical investigations, one can determine the soil’s bearing capacity—which is crucial in selecting a foundation that can adequately support the imposed loads without excessive settlement or failure.

Structural Load Requirements

The nature and magnitude of the loads imposed by the structure—whether it’s from the building itself, occupants, or external factors like wind and seismic activity—play a vital role in foundation choice. A structure with heavy loads might require a deep foundation, whereas lighter structures can be supported with shallow foundations.

Site Constraints and Accessibility

Every construction site is unique, presenting its set of challenges. The presence of nearby structures, utilities, and other obstacles can restrict foundation choices. In addition, if the site is hard to access, it might not be feasible to bring in large equipment needed for certain foundation types—requiring alternative solutions.

Environmental Considerations

The environmental impact of construction activities is becoming an increasingly vital consideration. Areas with high water tables, for example, might require special foundation types to prevent groundwater contamination. Similarly, in ecologically sensitive areas, minimal disturbance techniques might be preferred.

Budget and Time Constraints

Every project operates within a budget and timeline. Deep foundations, while offering superior load-bearing capacities, tend to be more expensive and time-consuming than their shallow counterparts. It’s ideal to strike a balance between the foundation’s technical requirements and the project’s financial and temporal constraints.

The selection of a foundation type is a multifaceted decision that demands a thorough understanding of the site, the structure, and broader project goals. With careful consideration of the factors listed above, contractors and engineers can ensure a foundation that’s robust, cost-effective, and environmentally sound.

Comparing and Contrasting Shallow and Deep Foundations

The choice between shallow and deep foundations is influenced by various factors—including the nature of the structure, site conditions, financial considerations, and much more…

Purpose and Application

Shallow foundations are best suited for lighter structures. The proximity of the bedrock to the surface often determines the use of shallow foundations. When the bedrock is near, it can provide the necessary support for the structure—eliminating the need for a deeper foundation.

Deep foundations are the go-to for heavy structures or in situations where the upper soil layers are too weak or inconsistent to bear the structural load. In such cases, the foundation needs to bypass these layers and transfer the load to deeper, more competent strata.

Depth

Shallow foundations usually don’t go beyond 3 meters in depth. The essence of these foundations is to spread the load horizontally, using the width to distribute the forces.

As the name suggests, deep foundations delve deep—often extending tens of meters below the ground. They aim to transfer structural loads vertically downward to layers of soil or rock that have adequate bearing capacity.

Soil Interaction

The effectiveness of shallow foundations largely depends on the bearing capacity of the soil near the surface. They work by dispersing the structural load over a broad area, ensuring that the weight is well-distributed and supported by the topsoil.

Unlike their shallow counterparts, deep foundations aren’t reliant on surface soils. They function by transferring loads to far deeper, stable layers or even to bedrock. This ensures that the structure remains secure, even if surface soils are unstable or weak.

Installation Time and Cost

One of the advantages of shallow foundations is the relatively quick and cost-effective installation process. Without the need for specialized equipment or deep excavations, construction can proceed quickly.

Installing deep foundations is more complex and time-consuming. Specialized equipment, such as pile drivers and drilling rigs, is essential. This naturally incurs higher costs and longer construction times.

Flexibility and Adjustments

Shallow foundations allow for a degree of flexibility during the construction phase. Adjustments can be made relatively easily if there’s a change in the building plan or if unforeseen site conditions arise.

While they offer robustness and stability, deep foundations necessitate meticulous planning. However, they do offer some leeway for post-construction adjustments—especially with certain types like screw piles.

Common Mistakes and Pitfalls with Foundations

The choices made regarding shallow and deep foundations shouldn’t be taken with a “once-size-fits-all” approach. These decisions require a comprehensive understanding of the project’s requirements, site conditions, and budgetary constraints. The consequences for neglecting or misunderstanding these factors can be disastrous. That being said, here are some of the most common mistakes made and pitfalls encountered with foundations…

Shallow Foundations

- Inadequate site investigation: Failing to properly investigate the soil conditions can lead to selecting the wrong type of foundation for the site’s characteristics.

- Ignoring water table levels: Building in areas with a high water table without proper drainage can lead to foundation instability due to soil liquefaction.

- Inadequate compaction: If the soil isn’t compacted properly, it can settle over time—leading to foundation movement and potential damage.

- Oversizing the foundation: While it might seem like a larger foundation would provide more support, it can lead to unnecessary costs and potential issues if not designed properly for the structure it supports.

- Neglecting drainage: Proper drainage is crucial to prevent water accumulation near the foundation, which can cause issues like hydrostatic pressure and soil erosion.

Deep Foundations

- Poor pile installation: If piles are not driven or placed correctly, they might not bear the loads as intended—compromising the structure’s stability.

- Inaccurate depth estimation: Not extending piles to the appropriate depth or layer can reduce their load-bearing capacity.

- Ignoring lateral loads: Deep foundations, especially piles, need to be designed not only for vertical loads but also for lateral loads due to wind or seismic activity.

- Using incorrect equipment: Utilizing equipment that’s not suitable for the specific type of deep foundation being installed can lead to structural problems down the line.

- Overlooking pile testing: It’s crucial to test piles for their load-bearing capacity. Skipping or incorrectly performing these tests can result in inadequate foundation support.

Conclusion

The delicate balance between shallow and deep foundations, as discussed throughout this article, highlights the significance of methodical planning and keen understanding in construction projects. While each foundation type offers unique attributes and benefits, it’s not merely about selecting one over the other. The true essence of a successful project lies in thorough investigation, understanding the specific characteristics of the site, and ensuring that the chosen foundation aligns with these characteristics.

It’s imperative to recognize the broader landscape of considerations, from soil interactions to flexibility demands. The most successful foundation projects meticulously pay attention to detail, utilize the appropriate methods, and deploy the right equipment.

View the complete article here.

What are the key factors to consider when choosing between shallow and deep foundations for a construction project?

Factors include soil type and bearing capacity, structural load requirements, site constraints, environmental considerations, budget, and time constraints.

What are common mistakes to avoid in shallow and deep foundation projects, and how can they impact construction outcomes?

Mistakes include inadequate site investigation, neglecting water table levels, poor compaction, oversizing foundations, neglecting drainage for shallow foundations, and issues like poor pile installation and inaccurate depth estimation for deep foundations. These can lead to instability, settlement, and structural problems if not addressed.