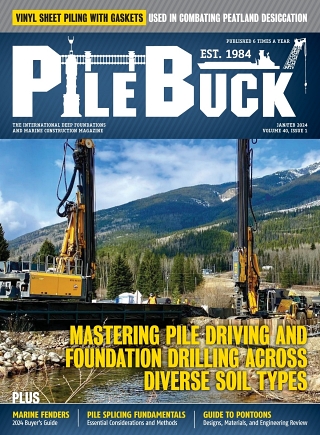

Challenges of Drilling High-Strength Rock in Deep Foundation Projects

Deep foundation construction often depends on predictable subsurface conditions, yet some of the most disruptive challenges emerge when drilling encounters high-strength or abrasive rock. These formations can slow production, increase tool wear, and introduce alignment issues that affect both structural integrity and project schedules. Understanding how and why these challenges occur is essential for selecting appropriate drilling approaches and minimizing risk on complex foundation projects.

Understanding High-Strength Rock Conditions

High-strength rock formations include dense igneous rock, hard metamorphic layers, and well-cemented sedimentary rock that resist penetration. These materials often exhibit high compressive strength, low fracture frequency, and abrasive mineral content. When encountered during foundation drilling, they behave very differently from soils or weathered rock, requiring adjustments to drilling methods and equipment.

Geological Factors That Increase Drilling Difficulty

Rock hardness alone does not define drilling complexity. Grain structure, mineral composition, and degree of fracturing all influence how drilling tools interact with the formation. Massive, unfractured rock can limit cutting action, while abrasive minerals accelerate wear on cutting surfaces. Variability within a single borehole can further complicate drilling by causing uneven resistance and tool instability.

Why These Conditions Matter for Foundations

Deep foundations rely on accurate depth, alignment, and bearing conditions. When drilling performance degrades in high-strength rock, it can compromise borehole geometry and lead to delays or corrective work. These challenges highlight the importance of matching drilling techniques to subsurface conditions rather than relying on a single approach across all ground types.

Why Conventional Augers Struggle in Hard Rock

Conventional augers are widely used for soil and softer rock formations, but they often reach practical limits when encountering high-strength rock. Their cutting edges are designed for shearing and conveying material rather than crushing or fracturing dense formations.

Limitations of Cutting and Material Removal

In very hard rock, auger teeth may fail to penetrate efficiently, leading to slow advance rates and excessive torque demands. Instead of cutting cleanly, the auger may grind against the surface, generating heat and accelerating wear. This reduces productivity and increases the likelihood of tool damage.

Effects on Borehole Quality and Alignment

As resistance increases, augers are more prone to deviation and chatter. These effects can result in irregular borehole walls and misalignment, which are unacceptable for many deep foundation applications. Maintaining verticality becomes increasingly difficult as drilling forces rise and cutting efficiency declines.

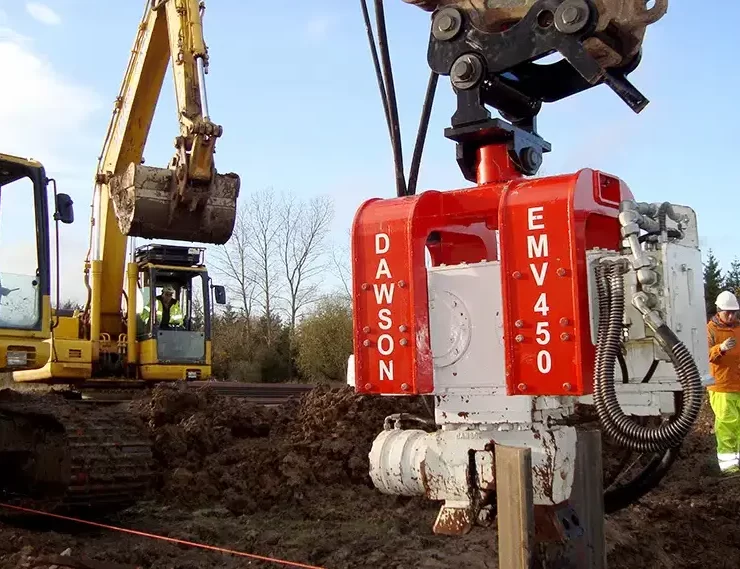

When Coring Methods Become Necessary

When augers can no longer advance effectively, coring techniques are often introduced to continue progress through high-strength rock. These methods remove material by cutting a circular path and isolating a core, allowing controlled penetration in dense formations.

Advantages of Controlled Rock Removal

Coring allows drilling crews to focus cutting action on a defined perimeter rather than the full bore diameter. This approach reduces resistance and improves control when dealing with hard or abrasive rock. Coring techniques are commonly used in situations where maintaining borehole geometry and alignment is critical for foundation performance.

Application in Deep Foundation Construction

In deep foundation projects, coring is often employed to extend shafts to design depth or to socket foundations into competent rock. The ability to progress through difficult formations while preserving borehole stability makes these approaches essential in many urban and infrastructure projects. General information on these techniques can be found through resources discussing rock coring methods used in foundation drilling.

Operational Risks in Hard Rock Drilling

Drilling through high-strength rock introduces a range of operational risks that must be managed carefully. These risks affect equipment longevity, project timelines, and overall construction quality.

Accelerated Tool Wear and Maintenance Demands

Abrasive rock formations rapidly wear cutting components, increasing maintenance frequency and replacement costs. Worn tools also reduce drilling efficiency, compounding delays and increasing operational stress on drilling rigs. Proactive tool selection and monitoring are essential to controlling these effects.

Deviation and Loss of Borehole Control

As drilling resistance increases, maintaining straight and stable boreholes becomes more challenging. Deviation can lead to alignment issues that compromise load transfer or require corrective measures. In deep foundations, even small deviations can have significant structural implications.

Productivity Loss and Schedule Impacts

Slow penetration rates and frequent stoppages for tool changes or troubleshooting can disrupt project schedules. In large foundation programs, cumulative delays can affect sequencing and coordination with other construction activities, increasing overall project risk.

Managing the Transition From Augering to Coring

Successfully navigating hard rock conditions often depends on recognizing when to transition from conventional augering to coring techniques. This decision is influenced by penetration rates, torque levels, and observed tool performance.

Indicators That a Change Is Required

Reduced advance rates, excessive vibration, and visible tool wear are common signs that augering is no longer effective. Continuing with unsuitable methods can worsen borehole conditions and increase costs. Early assessment allows crews to adapt before significant delays occur.

Planning for Mixed Ground Conditions

Many sites feature alternating layers of soil, weathered rock, and hard rock. Effective drilling strategies account for these transitions by incorporating flexible approaches that can adapt as conditions change. This planning reduces downtime and improves overall drilling efficiency.

Implications for Deep Foundation Project Success

High-strength rock conditions present unavoidable challenges, but their impact can be managed through informed decision-making and appropriate drilling techniques. Recognizing the limitations of conventional methods and understanding when alternative approaches are required helps protect project quality and timelines.

Importance of Matching Methods to Conditions

No single drilling method is suitable for all subsurface environments. Selecting techniques based on verified ground conditions improves predictability and reduces risk. In deep foundation construction, this alignment between geology and drilling approach is essential for achieving design intent.

Long-Term Benefits of Proper Technique Selection

Although coring approaches may involve higher upfront effort, they often reduce long-term costs by improving productivity and minimizing rework. Access to well-designed deep foundation drilling equipment supports safer operations and more reliable outcomes in demanding rock conditions.

Key Considerations For Hard Rock Drilling

Deep foundation projects that encounter high-strength rock demand careful planning, adaptable drilling strategies, and an understanding of the limitations of conventional tools. By anticipating these challenges and applying appropriate methods, contractors can maintain control, protect equipment, and deliver foundations that perform as intended under the most demanding subsurface conditions.