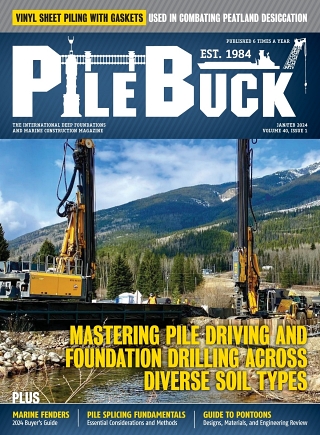

Why Mixed Soil-to-Rock Transitions Are the Most Difficult Phase of Overburden Drilling

Overburden drilling becomes most unpredictable at the point where soil abruptly gives way to rock. Contractors routinely report that installations progressing smoothly through sands, clays, or gravels can suddenly encounter refusal, deviation, or tool damage once bedrock is reached. These soil-to-rock transitions concentrate multiple geotechnical challenges into a very short drilling interval, making them one of the highest-risk phases of foundation installation in marine and heavy civil work.

Subsurface Variability and Drilling Uncertainty

Subsurface profiles rarely present clean, horizontal boundaries between soil and rock. Instead, drilling often encounters sloping bedrock, weathered rock lenses, boulders, or fractured rock zones embedded within dense soils. This variability creates uncertainty in tool performance, cutting efficiency, and load transfer at precisely the moment when drilling conditions are changing most rapidly. In mixed ground drilling, even small changes in formation hardness can significantly alter torque demand and bit behavior, increasing the likelihood of operational instability.

How Drilling Tools Respond at Soil-to-Rock Interfaces

Sudden Changes in Formation Resistance

Drilling tools designed for soil operate under fundamentally different assumptions than those intended for rock. When a cutting tool transitions from soft or granular material into competent rock, resistance increases sharply over a very short distance. This sudden load spike can overwhelm tooling that lacks the ability to adapt to higher compressive strength, leading to slowed penetration, vibration, or mechanical failure.

Loss of Tool Stability and Control

At soil-to-rock interfaces, partial contact between the cutting face and the formation is common. One side of the tool may still be cutting soil while the opposite side engages rock. This uneven resistance creates asymmetric forces that can push the tool off line. Without adequate stabilization, this imbalance can initiate borehole deviation, particularly in foundations requiring strict alignment tolerances.

Why Conventional Augers and Standard Bits Struggle

Limited Effectiveness in Hard Transitions

Conventional augers perform efficiently in cohesive soils and loose overburden, but they are not designed to penetrate competent rock. When augers encounter bedrock, cutting teeth often skate across the surface or experience accelerated wear. Repeated attempts to force penetration can damage tooling and enlarge the bore unevenly, compromising borehole geometry.

Increased Risk of Refusal and Tool Damage

Standard drilling bits face similar challenges at transitions. Bits optimized for rock may advance too aggressively in soil, while soil bits lack the cutting structure needed for rock penetration. The result is often refusal at the transition point, accompanied by elevated torque, vibration, and heat generation. These conditions increase the likelihood of cracked welds, broken teeth, and premature tool replacement.

Borehole Geometry Risks During Transitions

Diameter Irregularities and Wall Instability

Maintaining consistent borehole diameter becomes difficult when cutting mechanisms are not suited to both materials. Undersized sections can increase casing friction and installation force, while oversized zones can reduce lateral confinement and compromise load transfer. These geometry issues are particularly problematic in deep foundations where casing advancement depends on predictable wall conditions.

Deviation and Structural Consequences

Deviation initiated at soil-to-rock transitions can persist throughout the remainder of the installation. Even small angular changes at depth may result in piles or shafts missing design tolerances at the surface. In bridge, marine, and utility foundations, such misalignment can lead to costly remediation or rejected installations. Selecting appropriate rock drilling methods for these transitions is therefore critical to maintaining structural performance.

The Role of Controlled Underreaming in Mixed Ground

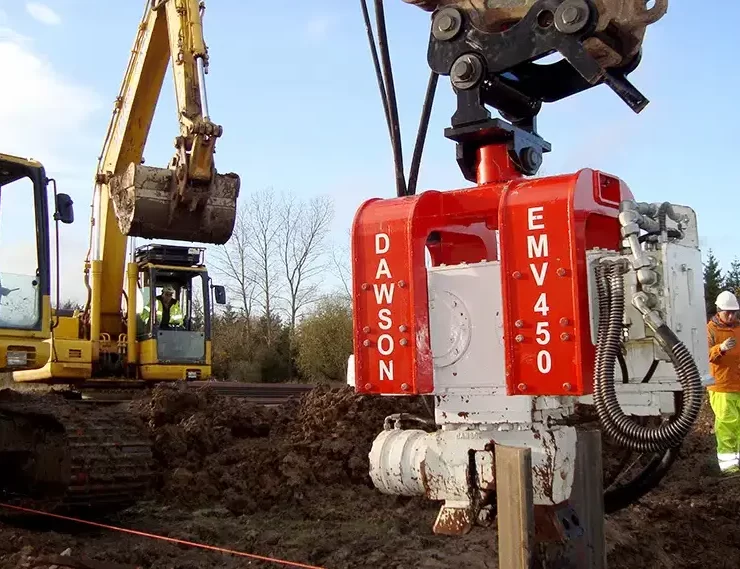

Managing Diameter Through Variable Formations

Controlled underreaming allows contractors to stabilize borehole diameter as formations change. By enlarging the hole in a controlled manner at the transition zone, contact pressure between casing and formation is reduced. This approach helps mitigate friction spikes and allows casing to advance smoothly even as drilling resistance increases.

Improving Stability and Alignment

Underreaming can also help rebalance cutting forces when encountering uneven rock surfaces. By engaging the formation uniformly around the borehole circumference, the risk of lateral deflection is reduced. This improves alignment control and minimizes the chance of deviation initiated by asymmetric rock contact.

Risk Mitigation Strategies Contractors Use

Advance Investigation and Tool Planning

Experienced contractors rely heavily on detailed subsurface investigation to anticipate transitions. Core logs, geophysical surveys, and prior project data help identify likely transition depths and rock quality. This information allows drilling teams to plan tooling changes and operational adjustments before reaching critical zones.

Adaptive Drilling Sequences

Many crews adjust rotation speed, feed pressure, and flushing parameters as transitions approach. Slowing penetration rates and increasing monitoring during this phase can help detect early signs of instability. In some cases, contractors stage drilling operations to allow for tooling changes specifically at the soil-to-rock interface.

Emphasis on Retrievable and Reusable Tooling

In sensitive marine or urban environments, leaving sacrificial components in the ground may not be acceptable. Retrievable systems reduce environmental impact and allow contractors to adapt tooling configurations if conditions differ from expectations. This flexibility is particularly valuable when dealing with unpredictable mixed formations.

Why Transitions Deserve Standalone Attention

Mixed soil-to-rock transitions compress multiple drilling risks into a narrow depth interval. They combine sudden strength changes, variable geometry, and high alignment sensitivity in ways that pure soil or pure rock drilling does not. Treating transitions as a distinct phase of overburden drilling rather than an incidental challenge allows contractors to plan more effectively, reduce downtime, and protect both tooling and structural outcomes.

As foundation projects continue to push into more complex subsurface conditions, understanding and managing these transition zones will remain a defining factor in successful overburden drilling operations.